Where's the picture?

Well, it's been a great Christmas and

New Year's holiday at the observatory. That would be all except the

clouds and rain. Six inches plus of rain. Finally, on January 5th

I was able to get back under the stars and see them. It was cold,

however. The thermometer on the scope registered 18 degrees F at 9:30

when I came in. Never fear, though; I wasn't out the whole time. I

used the Starlight Network to sit in front of the TV, nice and warm,

while I let the scope, camera, and computer do it's thing; I just

monitored it all. That's my idea of a good way to image. It's taken

only 13 years to get to this point. My patience has been rewarded.

Well, on to the current image, which is IC342 located in the

constellation of Camelopardalis. That's a mouthful. Translation, the

Giraffe. This is not a constellation from ancient Greek times, but

from about 1613. From Wikipedia “Camelopardalis was created by

Petrus Plancius in 1613 to represent the animal Rebecca rode to marry

Isaac in the Bible.[1] One year later, Jakob Bartsch featured it in

his atlas. Johannes Hevelius gave it the official name of

"Camelopardus" or "Camelopardalis" because he saw

the constellation's many faint stars as the spots of a giraffe.[7] “

IC342 is a galaxy, very faint, of course, about 7 to 11 million

light years from earth. This one pushed the scope, which has an 8

inch aperture, pretty much to the limits for my geographical

location. By that, I mean that the skyglow was getting uncomfortably

close to the glow from the galaxy. Allow me to demonstrate.

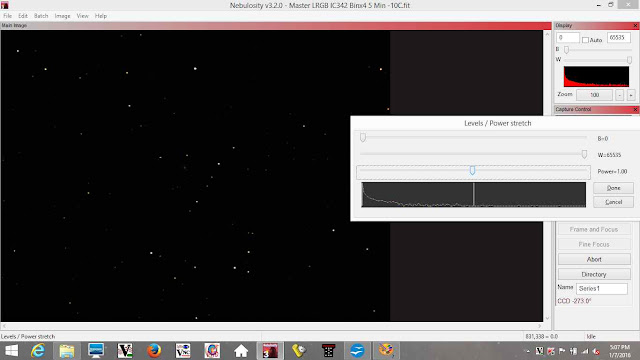

What you see above is the image of the

galaxy after all the calibration frames have been applied and the

luminance, red, green and blue channels have been added together, but

before any level adjustments have been applied. The program I'm

working in is Nebulosity, and this is the work screen shot showing

the image and some information on the image. What you see in the

image section are the foreground stars (those stars between us and

the galaxy).

In the screen shot above, I've

highlighted the histogram. It took me a long while to get used to

working with a histogram, but now it's more or less second nature.

What the histogram shows is the number of pixels of a particular

value. That's rather general, so let's look at this histogram. The

red part of the histogram tells me the relative number of pixels that

have a 0 (zero) value on the far left of the histogram and a value of

37440 on the far right (and everything in between). A pixel of value

0 is a black pixel. As the value of a pixel increases, in becomes

brighter white, so to speak. From this histogram, we can see that

there is a lot of pixels nearer to 0 than 37440. As is the case with

most images of the night sky, that's what we would expect; there's a

lot more black than white. I can also tell that, if the image

of the galaxy exists, it's in the group of pixels at the far left

end. Another way of looking at it, no pun intended.....well, maybe,

is that the information I want to show is in the group of pixels at

the far left end. My goal, will be to use the image tools in

Nebulosity to spread the small range of values at the far left end

out, and into as wide of a range as I can and still have the image

look reasonable. Whatever the final range of values, what I want is

to see the histogram look as nearly flat, like the top of a cake, as

I can get it, instead of seeing a histogram with the graph looking

like it does now, with a sharp peak at the left side and little on

the right.

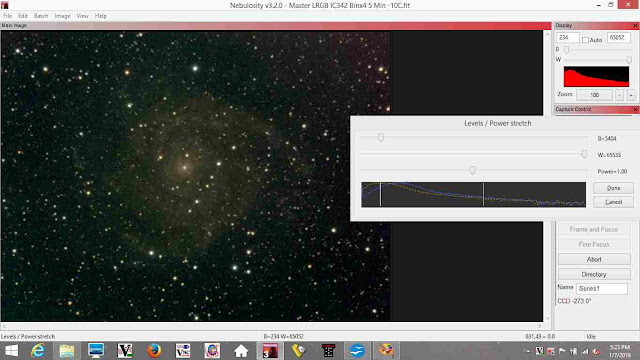

What I've done is bring up the “levels”

adjust dialog box. Notice that the graph there is essentially

identical to the histogram in the upper right corner. What I will do

is make a series of changes in the "levels" dialog and show

the results. Follow along, if you want.

Notice that I've move the “power”

slider to the left and the result in the image is that it is now

lighter, like turning up the brightness.

Now I've closed the original "levels"

dialog box, opened another and moved the black slider to the right.

See how the image is now a little darker than the previous one, but,

more importantly, the graph (both the histogram and the one in the

"levels" dialog box) are starting to spread out. It will

never be completely flat, but lets see what we can do.

I've done exactly the same thing (ie,

opening a "levels" dialog box, moving the power slider to

the left, closing, opening a new "levels" dialog box,

moving the black slider to the right) 2 more times. As you can see,

the histogram is much flatter, and the galaxy is starting to emerge

from the background.

I've done exactly the same thing (ie,

opening a "levels" dialog box, moving the power slider to

the left, closing, opening a new "levels" dialog box,

moving the black slider to the right) 2 more times. The galaxy is

clearly there, but looks rather rough. That's about all I can do with

the histogram for now. What happens next will be something like...

blur the image (the noise in the image is less organized than the

galaxy, so blurring will help to get rid of it when I sharpen the

image.), then sharpen, remove any residual background color problems

(color cast), increase contrast, and so on until I'm happy with the

image. After all that, the best I think I can get from this image

looks like:

I hope you enjoyed the journey.

No comments:

Post a Comment